+++

Jennifer Callaway’s ‘No Ground,‘ commissioned for the Radia network’s first broadcast of 2023, is a composition that takes a single 27 minute live improvised recording of a 1940s Bakelite valve radio, and subtly weaves this instrumental base into a patterned sonic fabric with several other musical and sonic elements. It is a delicate meditation on radio as instrument and channeller of the unknown, and a dual love letter to the medium’s long histories of domestic sonic use and its role as gateway to sonic experimentalism.

Jen told me when we were talking about a Radia commission that she hadn’t done a solo piece before. Given her many decades of creative output, at first this fact seemed surprising – even monumental – then I realised it was contingent on how we classify the singular. As an improviser, her tendency is to work in collaboration, with care to nurture her human and nonhuman connections; to instigate and to maintain what we could potentially call a conversation as much as an ecosystem. This alchemical yet everyday process is one that involves the passing and circulation of energy and an equilibrium of intention, as well as the robust embrace of the accidental.

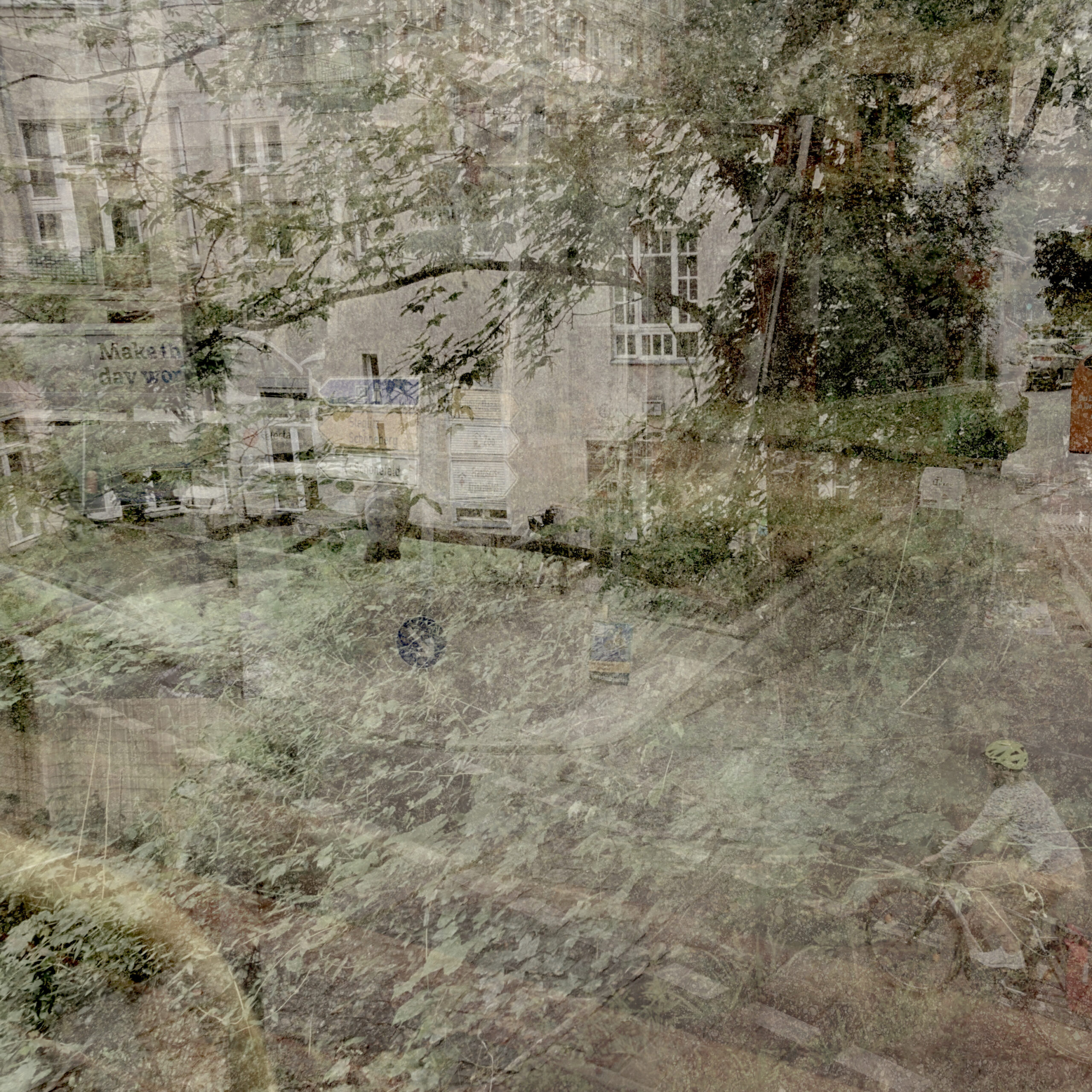

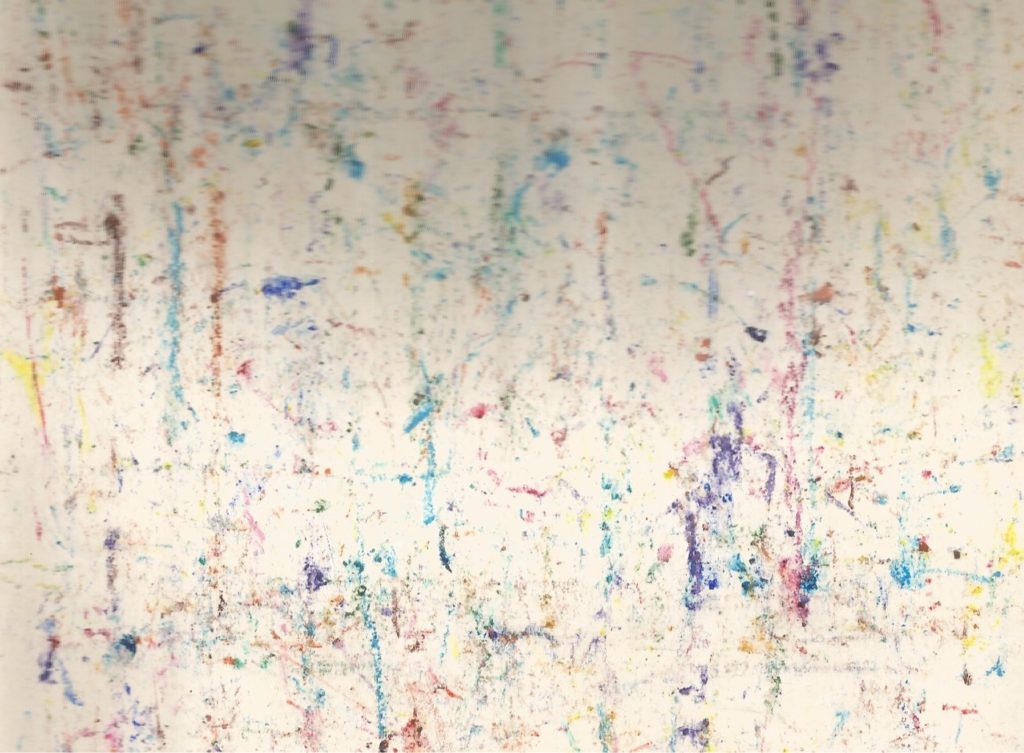

Callaway’s sonic palette – as a concrète auteur of the current Melbourne improvised and experimental music scene – is resolutely grounded in the poetics of immediacy, the responsive, living moment of connection – with musical collaborators in collectives Snacks, Hi God People, Propolis and the duo Is there a Hotline?, and also with her photographic practice that traffics in the aesthetics of the blur: a collaboration with light and time, a yearning toward some aesthetic that revisits the wonder and experimentalism contained at the chemical dawn of the photographic process itself, coupled with a poet’s ability to perceive the life within the materials of the ostensibly insensible – within the grain of the table, the ghost of the living wood.

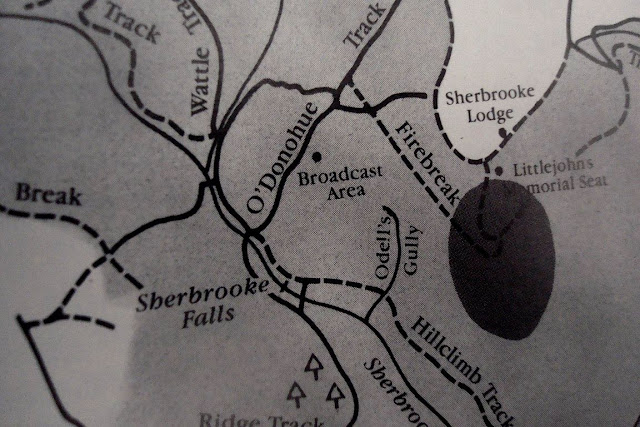

And here she is, not in solo capacity at all, but working with the radio as collaborator. This particular radio is one of my instruments within the radio cegeste menagerie; it’s a vintage Australian STC from the late 1940s with a beautiful warm valve sound, a great dynamic range, and many unknown histories. At some point both its aerial and its earth wire were cut off, so its ability to act as a receiver is limited. It has likely outlived some of its owners who also wandered its dial in the mid twentieth century, at a time when radio was fully centralised in culture, searching for information or entertainment, some human anchor for the ear, but it is also likely that they encountered its particular tonal translation of the vast seas of static between these islands, the pop and crackle of the inhuman, the unknown and the ancient.

Lending your tools to another artist is instructive, especially when that instrument is uncommon. It does much to cast light on the use of instrumentation within artistic process, and often leads (again) to the revelation that the technique or the tool is not the art itself (aka “don’t mistake the tools for the purpose”). As such, as much as I know these sounds, the rhythms, movements and temporal clusters that emerge from Jen’s use of this particular radio as a compositional tool are not the ones I would have chosen. They are another conversation with radio’s domestic and material pasts, its temporal immediacies, and its potential futures. I would have spoken to these as well, but differently. I recognise a musicality in No Ground that is completely Jen’s.

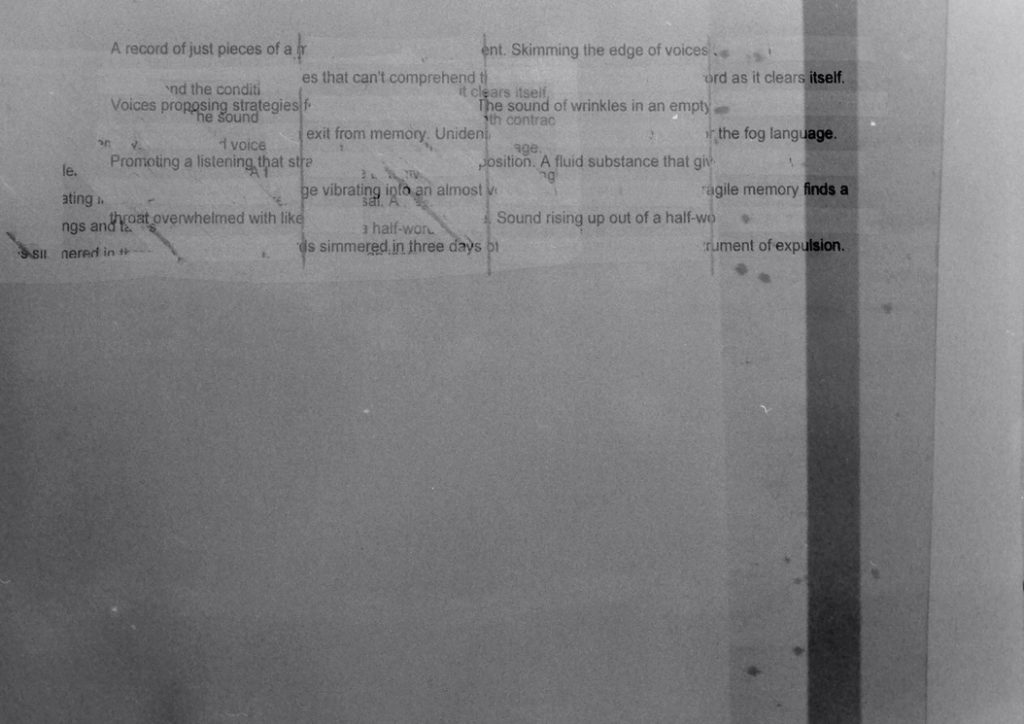

She wrote a statement about the piece that illuminates this further: “Is there anybody out there…….? Returning to my 1970s childhood love of rolling through the radio wave ether of space junk, disturbed psyches (akin to mine ?) and wistful echoes with a slow motion comb, greeting each shocking encounter with a little tickle and a dance. Back then, I would climb up on the kitchen bench to reach the shelf where the small radio in its brown leather-bound case spent most of its time (next to the “good” scissors). This time around, I had the wonderful privilege of borrowing my friend Sally’s art deco bakelite valve radio, at her suggestion. And I had the means to weave in a small number of additional imagined voices.”

From 1997 until the early 2000s I hosted a late night experimental radio programme on my local student radio station, RDU 98.3FM, in Christchurch, New Zealand, called Rotate Your State. The ‘sting’ I used for the show was a modified section of Stockhausen’s Hymnen (1966-67), notable for its browsing of the musicality of the shortwave radio dial, a restless, echoic, tearing, twisting, turning and re-turning. This openness was offset by the presence of national anthems that intruded like interference through the piece, a series of quotational presences, the thresholds of declarative nationalisms conflicting with the borderless sense of planet that attended the use of radio space, the ungrounded sea of the wider composition. Stockhausen said that one of the ideas behind the use of these national anthems was to have them act as “signposts” for listeners, as they travelled through an unknown world of sound, noise and disconnected voices, that “everyone knows the anthem of his own country, and perhaps those of several others, or at least their beginnings.”

To ‘ground’ an analogue radio is to earth it, with this process located somewhat literally in the geographic; the ultimate goal being to locate a local frequency bandwidth signal. An improperly earthed radio wanders the dial, never able to fully fix down on one location; it might pick up several signals at once, or none at all. Many contemporary transmission artists and composers have become enamoured with such indeterminate phenomena, in the context of living in the world of digital radio (which in a cultural sense is still radio, but in a material sense is arguably not radio at all), dialing back into the histories of radio through its potential as a physical medium, re-learning the lessons first encountered by the earliest amateurs and their crystal sets, hearing again the sound of the first violin transmitted on the night airwaves, or the frail morse of a maritime signal speaking across the as-yet unlanguaged sea. Here, we are collectively listening back beyond Stockhausen’s Hymnen, which in its prescient beckoning to a global geopolitics in a polyphonic entanglement of nationalisms, was nevertheless a high Modernist composition, grounded within the signals provided by their translation into the anthemic – and the monolithic cultural position of the radiophonic. This itself might be one key to listening to Jen’s composition No Ground, as it joins this conversation. A mobility and precariousness found in our contemporary media ecologies moves back into the analogue; the dial is now an ungrounding, that resists the very idea of the signal as a resting place within the sea of noise, it playfully flutters around it, it speaks back to the everyday droning voices found there with not a small amount of humour and transforms them through active listening, not for sense but for sound. It is resolutely un-earthed.

Jen writes that she partially learnt her own sonic ungrounding through radio – that drifting around the radio dial as a child provided hours of wonder, and No Ground is a representation of that curiosity and grasp of accidental mysteries, filtered through decades of dedicated performing and listening to, and being involved with experimental music communities. Within the composition, radio can be grasped in its current material immediacies, a counter-earthing that recalls and revitalises its own histories of what it has been; in its end is its beginning: the fact that its dial is largely empty of signal in the early twenty first century harks back to the more expansive emptiness of the nineteenth, before the radio’s centralising within twentieth century culture and the media cultures of Modernity – on the edge of representation, it is also infused with its longer imaginaries: with the oceanic, with the powdery granular whispers of geological and atmospheric phenomena – the sounds of weather, of natural radio and the magnetosphere; with the insect scratch and bird-warble of the non-human, with the pressing, crowding, numinous voices of the dead, always just out of earshot.

Sally Ann McIntyre, January 2023.

++++

Jen Callaway is a Naarm/Melbourne (AU) based musician, sound and performance artist, and photographer, raised in various parts of Lutruwita/Tasmania. With a special interest in psychodynamics, hauntology and conservation, current projects include bands Is There a Hotline?, Propolis, Snacks and Hi God People.

https://linktr.ee/jencallaway

Credits:

Jennifer Callaway: composition, recording, editing, images

December 2022-January 2023